He said yesterday there were legitimate grounds for the court to accept the case even though its second vice president, Hans-Peter Kaul, said in Bangkok earlier this month that the case did not fall under the jurisdiction of the ICC because Thailand was not a state party to the Rome Statute, the treaty that established the court.

The lawyer said the violence in Bangkok, which resulted in the death of more than 90 people, should come under the ICC because the Rome Statute covers cases filed against persons holding the nationality of a country that is a state party to the ICC.

Mr Abhisit was born in the United Kingdom in 1964 and holds British nationality, Mr Amsterdam said. Britain ratified the treaty in October 2001.

Article 17 of the treaty also states that if the principle of due legal process does not exist in a country, the court shall consider the proceedings.

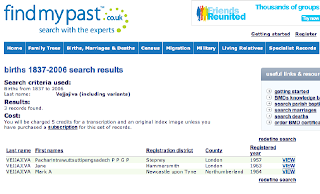

BP: On whether Amsterdam’s legal argument is correct is well beyond the scope of this blog, or at least for now beyond the scope of this post, and this post will simply try to determine whether Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva is a British citizen. According to Abhisit’s own website, he was born on August 3, 1964 in Newcastle. It appears his birth name is actually Mark Abhisit Vejjajiva as you can see from this website which has records of almost all British births dating back hundreds of years (Brits like to trace their family history) and confirms he was born in Newcastle in 1964.*

The UK Border Agency website states:

If you were born in the United Kingdom before 1 January 1983, you are almost certainly a British citizen. The only exception is if you were born to certain diplomatic staff of foreign missions who had diplomatic immunity.

Let’s get a bit more technical and specifically Chapter 2 of the Nationality Instructions on the UK Border Agency website which deals “with the status of people born before 1 January 1983″. The relevant part is below:

2.5.1 A person born in the United Kingdom (see Note B to Annex D) before 1 January 1983 may be regarded as a British citizen on production of:

• a passport issued on or after 1 January 1983 describing the holder as a British citizen; or

• a passport issued before 1 January 1983 describing the holder as a citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies and carrying an endorsement stating the holder has the right of abode in the United Kingdom; or

• a United Kingdom birth certificate showing parents’ details (but see also paragraphs 2.5.3 – 2.5.5 below)

…

2.5.3 Because of the terms of the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act 1914 and the British Nationality Act 1948, the person may not have been a citizen of the

United Kingdom and Colonies by reason of birth in the United Kingdom if, at the time of the person’s birth, the father was either a diplomat or an enemy alien.

2.5.4 If the father’s occupation is given on the birth certificate as “diplomat” or the description otherwise suggests it is of a “diplomatic” nature, we should determine whether the person had a claim to citizenship of the United Kingdom and Colonies.

2.5.5 If the birth took place in the Channel Islands during the German occupation in the Second World War and the father was German, we should determine whether the person had a claim to citizenship of the United Kingdom and Colonies.

BP: As his father is not German and of course his was not born during WWII, the enemy alien part is not applicable. Hence, as long as Abhsit’s father was not a diplomat, he was born a British citizen. Abhisit’s father was studying medicine in the UK around the time of Abhisit’s birth and he was working as a lecturer in Thailand which you can say by this biography on the Mahidol University website, where Abhisit’s father served as the President.

BP should note that there is no need to apply for British citizenship by birth, it is automatic. There is no registration, you are simply a citizen. Yes, he needs a birth certificate to prove he is a citizen, but that is just to prove his status.

Now, BP can’t see any reason how Abhisit was not a British citizen by birth and his aide Sirichoke seemingly confirms this per the Bangkok Post:

Democrat Party MP Sirichoke Sopha, a close aide to the prime minister, said Mr Abhisit renounced his British nationality a long time ago when he was a student in the UK.

Mr Abhisit does not hold a British passport and has to apply for a visa if he travels to the UK, Mr Sirichoke said.

BP: One cannot renounce citizenship of a country if one is not a citizen so this is confirmation. It is certain possible to renounce his British citizenship although this is a formal process where you have to fill in a form and pay a fee. Then, there is a formal record that you renounced your British nationality – see UK Border Agency website. Abhisit would then either have in his possession now or could obtain proof of renunciation. If he renounced it when he was a student this is before the crackdown, he would no longer hold British nationality so it means that the grounds on which Amsterdam is arguing the case can be heard no longer applies.

However, while Sirichoke is stating that Abhisit has revoked British citizenship, Abhisit himself is more vague per Matichon where he states he is a Thai citizen (ขอยืนยันถือสัญชาติไทย) and does no hold British citizenship as Robert Amsterdam states (ไม่ได้ถือสัญชาติอังกฤษตามที่นายโรเบิร์ต อัมสเตอร์ดัม). He also states that he when he was studying in the UK, he paid student fees the same as foreigners or when he goes to the UK, he needs a visa to enter (ระหว่างที่ศึกษาเล่าเรียนอยู่ที่ประเทศอังกฤษก็ต้องจ่ายค่าเล่าเรียนเหมือนคนต่างชาติทั่วไป หรือการเดินทางไปประเทศอังกฤษก็ต้องยื่นเรื่องขอวีซ่า)

BP: This seems like a non-denial denial except the part of him no holding British citizenship. That he is a Thai citizen is irrelevant to whether he is a British citizen by birth. That he did paid foreign fees could be because he did not submit the necessary evidence to qualify for lower fees. Not sure of the exact fee structure of British universities back then, but normally you need to prove you are a “local” and if he didn’t that doesn’t mean he was not a British citizen. Similarly, if Abhisit uses his Thai passport he needs some form of a visa to enter the UK. If he is a British citizen, he could apply for the right of abode stamp in his Thai passport, but if he does not, he needs some form of permission to enter.

However, other papers actually don’t quote Abhisit as specifically denying he is a British citizen. In fact, he just avoids answering. For example, Thai Rath and Khao Sod doesn’t have an exact denial from him, it just paraphrasing him as stating that he has ever used the benefits/rights of the UK and paid full fees and needs a visa to enter which is a separate question of him being a UK citizen.

BP: Not using the rights/benefits does not mean he is not a citizen although Abhisit is trying to answer carefully and makes BP wonder why that the reason he is being so careful is that he is still a British citizen. So did he renounce his citizenship as Sirichoke is quoted as saying? If so, just state so and show a copy and Amsterdam’s submission is in legal peril.

*Actually, you can order a copy of his birth certificate if you really want

UPDATE: A reader points out that even British citizens can pay the “overseas” fee when studying at British universities because the question of what fees you pay is not determined just by your nationality but whether you are “ordinarily resident” in the UK. The UK Council for International Student Affairs (UKCISA), the UK’s national advisory body serving the interests of international students and those who work with them, has more details:

The relevant residence area is specified in each individual category, and is one of the following:

* the UK and Islands

* the EEA and Switzerland

* the EEA, Switzerland and the overseas territories

* the EEA, Switzerland, Turkey and the overseas territories

You are ‘ordinarily resident’ in the relevant area if you have habitually, normally and lawfully resided in that area from choice. Temporary absences from the residence area should be ignored.

If you can demonstrate that you have not been ordinarily resident in the relevant residence area only because you were, or your ‘relevant family member’ was, temporarily working outside the relevant residence area, you will be treated as though you have been ordinarily resident for the period during which this was the case.

Main purpose of residence being full-time education

Where a category includes a condition that the main purpose of your residence must not have been to receive full-time education, a useful question to ask is: “if you had not been in full-time education, where would you have been ordinarily resident?”. If the answer is “outside the relevant residence area” this would indicate that the main purpose for your residence was full-time education. If the answer is that you would have been resident in the relevant residence area even if you had not been in full-time education, this would indicate that full-time education was not the main purpose for your residence in the relevant area.

And then also on UKCISA:

R v Hereford and Worcester County Council ex parte Wimbourne CO/174/83 (QBD)

The student in this case was a British citizen who applied to his local authority for an award for a degree course that started in September 1983. Both his parents were British and he was born in the UK in 1962. His father died when the student was four years old and his mother went to work in Trinidad, where the student went to school. In 1979, he returned to the UK, stayed with an aunt and uncle, and studied for his ‘O’ and ‘A’ levels at a technical college.

The local authority refused the award on the grounds that the student’s residence in the UK had, during the last three years, been wholly or mainly for the purpose of receiving full-time education. As Mr Justice Hodgson states in his judgment, “In arriving at this decision, the Authority bore in mind particularly that you undertook a full-time course at Herefordshire Technical College, concerning which you had made enquiries before leaving Trinidad, immediately on your arrival in this country and this was in fulfilment of a prior intention of resolving to continue your Advanced Level education in England, which involved attendance at a full-time GCE A level course aimed at securing consecutive admission to the full-time degree course which is the subject of your present application. Your return to Trinidad during the long vacations is also considered a factor in this connection”. In this case, the student did not argue that he was in the UK for any reason other than to receive full-time education.

BP: See a British citizen who is deemed to be only in the UK to receive full-time education pays the overseas fee – that case would have been around the same time that Abhisit was in the UK as well so it is not a case that the law has just changed. If Abhisit had not been studying in the UK, would he have been living in the UK is the question that would be asked at the time. Given he returned to Thailand after his studies and his family was in Thailand, it would not be surprising if it was concluded he was not ordinarily resident as the main purpose of residence was to receive full-time education. Hence, Abhisit’s statement that he paid the overseas fee is not a statement that he is not a British citizen…

ไม่มีความคิดเห็น:

แสดงความคิดเห็น